Yersinia pestis V antigen

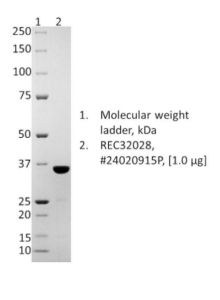

Yersinia pestis V antigen (LcrV antigen, capsule protein fraction 1, type III secretion system needle tip protein). The protein is produced as an N-terminal GST fusion, with GST. Our Yersinia pestis V antigen allows for further research into the immunisation strategy of this re-emerging infectious disease and the development of efficient, rapid diagnostic tools.

PRODUCT DETAILS –Yersinia pestis V antigen

- Yersinia pestis V antigen, pathowar Antigua

- NCBI Accession number: AAY23169.1

- GST capture and subsequent thrombin elution

- Expressed in E.coli

- Presented as liquid

BACKGROUND

Yersinia are gram-negative cocci acquired after ingestion of contaminated food or water. Y. enterocolitica is more frequently encountered than Y. pseudotuberculosis in the United States. Yersinia spp. are members of the Enterobacteriaceae. They are short, pleomorphic Gram-negative rods or coccobacilli, which often exhibit bipolar staining. Three taxonomic species of the genus Yersinia – Y. enterocolitica, Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis – cause human infections (Riahi et al., 2021).

Rodents are the main reservoirs of Y. pestis, known as the cause of the “Black Death”, an outbreak of plague which caused 50 million deaths in 14th-century Europe. (WHO, 2022).

Yersinia pestis is transmitted through flea bites or respiratory droplets. The bacterium spreads rapidly thanks to the highly successful infection strategy, including altering the mammalian immune response. It migrates to the hosts’ lungs resulting in pneumonic plague or lymph nodes causing bubonic plague (Demeure et al., 2019).

Pneumonic plague could be fatal within 18 hours of the disease’s onset; therefore, rapid diagnosis and introduction of appropriate antibiotics are crucial (Africa CDC, 2020). Currently, there is no FDA-approved vaccine against the plague for human use, although the research is ongoing since the Yersinia pestis has been classified as re-emerging threat (Feng et al., 2020). The infection rate is currently the highest since the 1990s, moreover, antibiotic-resistant strains of the disease have been reported, and the bacteria have been engineered as a potential biological weapon (Lei & Kumar, 2022).

REFERENCES

- Africa CDC (2020) Plague, Africa CDC. Available at: https://africacdc.org/disease/plague/

- Demeure, C.E. et al. (2019) ‘Yersinia pestis and plague: An updated view on evolution, virulence determinants, immune subversion, vaccination, and diagnostics’, Genes & Immunity, 20(5), pp. 357–370. doi:10.1038/s41435-019-0065-0.

- Feng, J. et al. (2020) ‘Construction of a live-attenuated vaccine strain of yersinia pestis EV76-B-Shuδpla and evaluation of its protection efficacy in a mouse model by aerosolized intratracheal inoculation’, Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 10. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.00473.

- Lei, C. and Kumar, S. (2022) ‘Yersinia pestis antibiotic resistance: A systematic review’, Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives, 13(1), pp. 24–36. doi:10.24171/j.phrp.2021.0288.

- Riahi SM, Ahmadi E, Zeinali T. Global Prevalence of Yersinia enterocolitica in Cases of Gastroenteritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Microbiol. 2021 Sep 2;2021:1499869.

- WHO (2022) Plague, World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/plague