Flaviviruses are a genus of positive-sense RNA viruses, largely transmitted by mosquito and tick vectors that cause infections, including yellow fever, dengue, the Zika virus, West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis, and tick-borne encephalitis. In fighting the emergence of flaviviruses, a well-established gap in our arsenal is the availability of accurate diagnostic data.

When infected by flaviviruses, patients can be asymptomatic or present with mild flu-like symptoms. However, in rarer cases, flaviviral infections lead to encephalitis, vascular shock, paralysis, congenital abnormalities, and death. While difficult to quantify, many flaviviral diseases are thought to be routinely under and misdiagnosed, leaving public health authorities with not only a poor picture of disease circulation, but impacting treatment and prognosis at the patient level.

Humans are mostly incidental dead-end hosts for flaviviral pathogens, with the majority of transmission occurring through complex enzootic cycles that include a range of animal, bird, and insect vectors and intermediary hosts. Factors such as climate change, population growth, and ecological disruption are driving the rapid emergence of many flavivirus vectors. As a result, the emergence of flaviviral diseases in recent decades has been remarkable: Flaviviruses are endemic in the majority of countries, with dengue estimated to cause upward of 400 million infections per year alone.

Flavivirus Serology

The underlying causes of the diagnostic data gap are many, with the limited resources of tropical and subtropical economies continuing to be a major factor. However, developing accurate means of flavivirus diagnosis has long been a challenge, even for more developed economies. Until recently, laboratory diagnosis relied on viral culture or reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction tests, which suffer from impracticalities and limitations due to the acute phase of infections, respectively. Because of this, serology has been extensively explored, with multiple serological markers to choose from, including:

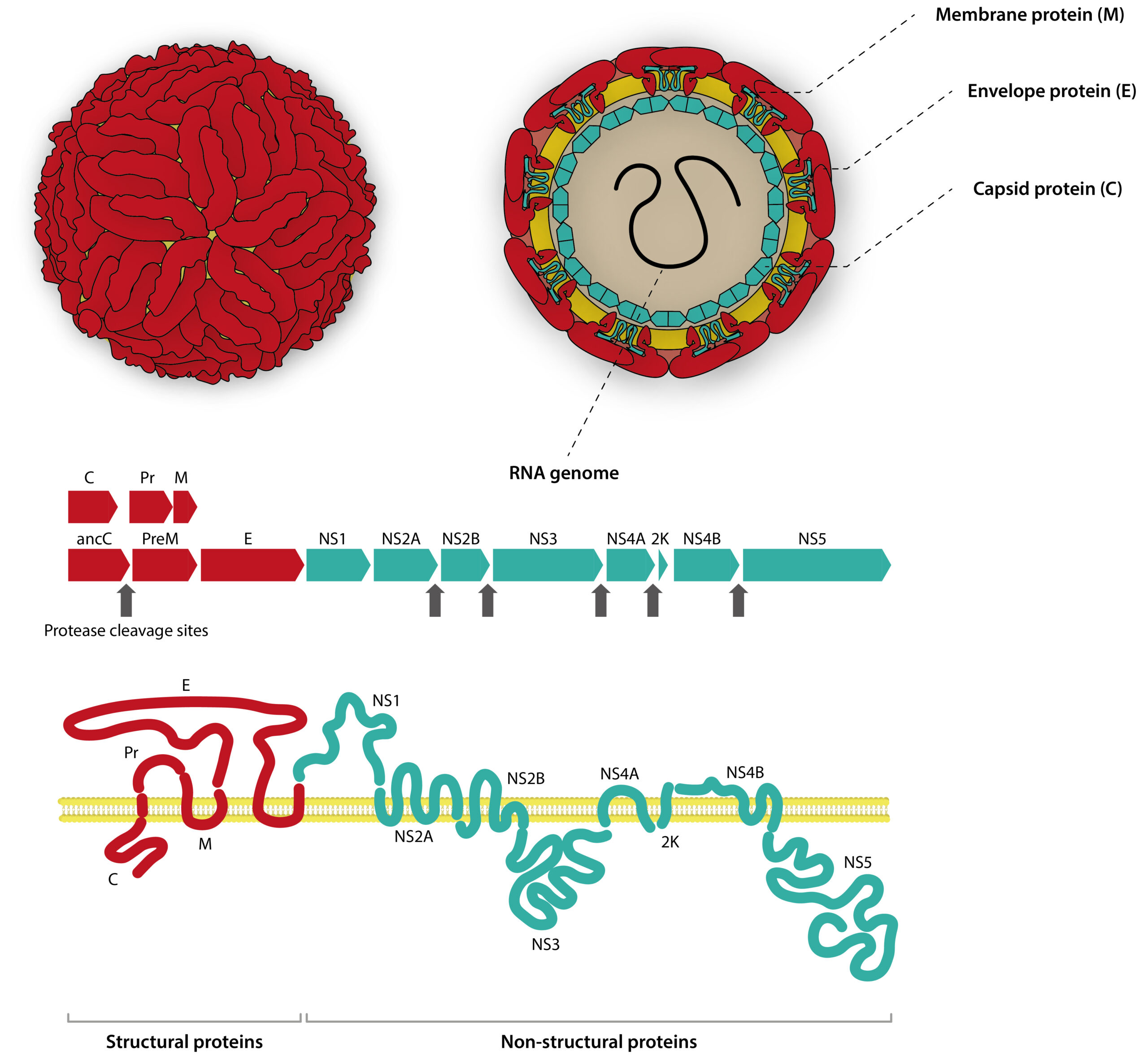

- Envelope (E) protein — the immunodominant target — which gives flavivirus virions their distinct “herringbone” appearance

- Pre-membrane (prM) protein

- Capsid (C) protein

- Nonstructural protein 1 (NS1), which exists in three distinct forms: an intracellular dimer, an extracellular dimer (mNS1), and a secreted extracellular hexamer (sNS1)

Diagram of flavivirus capsid, genome, and polyprotein structure, including key serological markers.

Improving Flavivirus Diagnostics

A central challenge in flavivirus serology is the close genetic relationships of co-circulating viruses and their serotypes, leading to cross-reactive antibody binding and false-positive results. Due to these issues, flaviviral immunoassays have long been plagued by poor specificity and false-positive results. Several presumed flavivirus infections therefore require a combination of initial and confirmatory techniques for which the necessary equipment and expertise is often limited.

Alternative immunoassay targets are increasingly being used due to the performance limitations of traditional serological diagnostics:

- Domain 3 (DIII) of the E protein contains a variety of important epitopes that are recognized by neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies. The epitopes in DIII are both highly conserved and highly variable, but through “epitope-focusing” mutational strategies, the structural fingerprints of the desired epitopes can be maintained while undesirable ones are ablated. This means that DIII can be used to discriminate antibody responses between flavivirus infections in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) with greater success than assays that use the whole E protein.

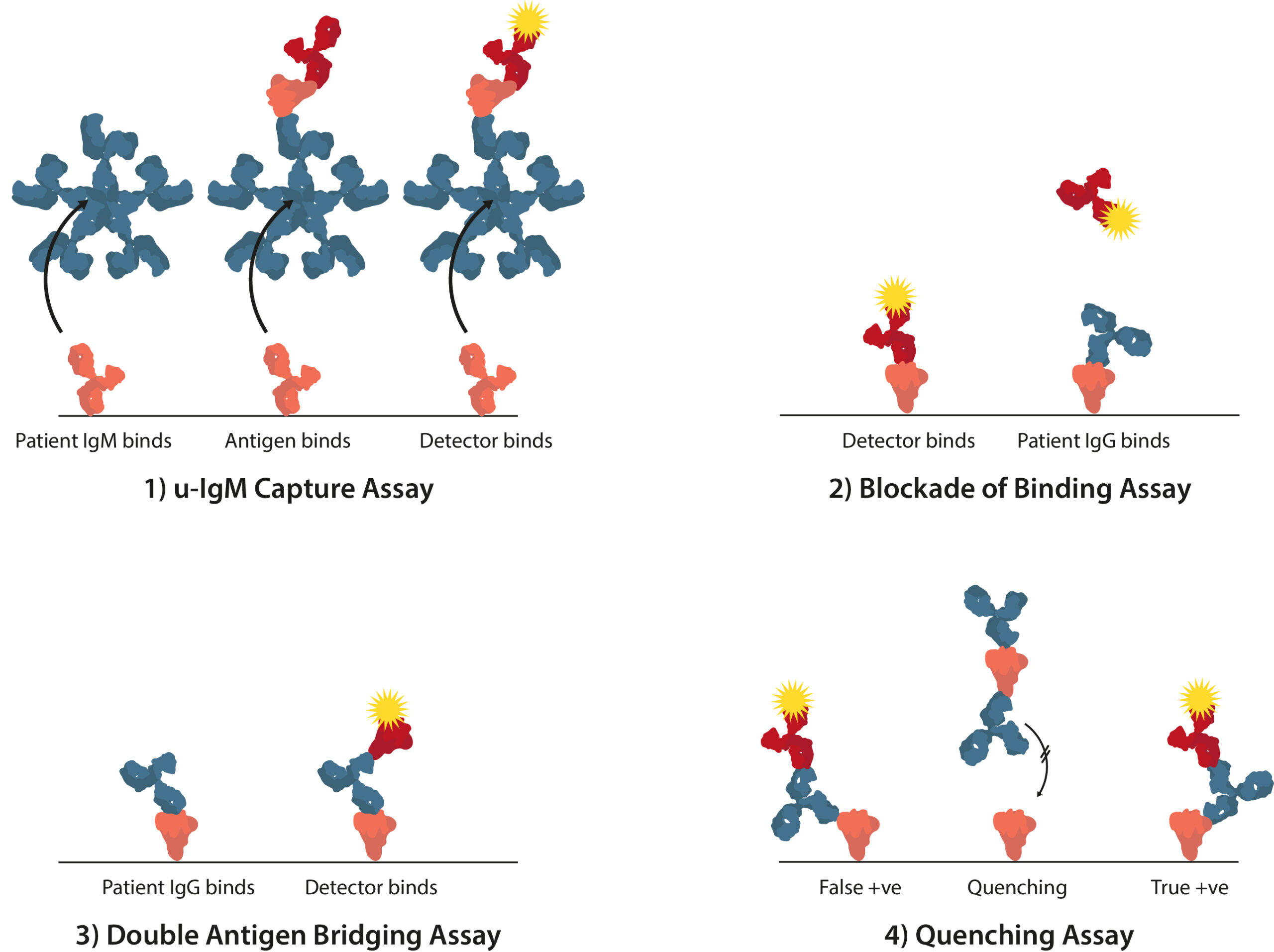

- Redesigning assay formats can also help to maximize performance parameters. For example, in traditional ELISA, a microtiter plate can be coated with anti-immunoglobulin M (IgM) immunoglobulin Gs (IgGs) to measure IgM levels in patients’ sera through antigen reactivity (µ-capture). However, these assays tend to be both complicated and lengthy. Novel alternative formats include the competitive ligand-binding assay “blockade of binding”; the double antigen bridging assay that uses an antigen sandwich, i.e., well-bound antigens bind patient sera antibodies followed by enzyme-labeled antigens, which enable antibodies to be detected with greater specificity; and the use of “quenching” antigens that absorb out cross-reacting antibodies.

- sNS1 has gained considerable attention as an effective surrogate of viraemia during acute phase infection, with many NS1 assays now commercially available. However, there are still some drawbacks in using NS1 for serodiagnosis because the antibodies produced can cross-react and are likely to clear from circulation within a week, offering only a brief diagnostic window.

Four alternative ELISA formats to mitigate ZIKV cross-reactivity include the 1) µ-IgM capture assay, 2) blockade of binding assay, 3) double antigen bridging assay, and 4) quenching assay.

Many flaviviral infections share symptoms, which means that differential diagnosis of multiple pathogens is highly valuable. An increasing amount of research is going into multiplex platforms that can capture a broader range of biomarkers to maximize sensitivity over all phases of flavivirus infections, from acute to recovered. Research has shown that high-density peptide microarrays and bead-based immunoassays are both sensitive and specific. However, other limitations remain, such as portability for use at or near the point of care and storage challenges, problems shared by traditional formats such as ELISA. On the other hand, formats such as dipsticks that detect NS1, IgG, and IgM show promise in meeting the divergent criteria of specificity and portability.

These strategies have shown initial promise in mitigating cross-reactivity and improving access in resource-limited settings. However, there is still work to be done to improve evaluation. While it is encouraging to see improvements in commercially available assays, claims on performance must be better substantiated through more rigorous independent studies and supporting data in order to confidently evaluate existing platforms.