Bovine Coronavirus

Bovine Coronavirus Background

BCoV transmission is horizontal, via oro-fecal or respiratory routes (Oma et al., 2016) resulting in both enteric and respiratory disease in both domestic and wild ruminants, including cattle, deer and camelids. In cattle, the infection causes calf enteritis and winter dysentery in adult cattle. It is also thought to be a member of the Bovine respiratory disease complex (BRDC), which is the major cause of serious respiratory tract infections in calves. Other viruses associated with the BRDC include bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV), bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BHV-1) and bovine parainfluenza virus type 3 (BPIV3). These diseases result in substantial economic losses and reduced animal welfare (Boileau & Kapil, 2010). Coronavirus infections may be complicated by parasite infestation (e.g., Cryptosporidia, Eimeria) or bacterial infections (e.g., E. coli, Salmonella) and are often a more severe and long-lasting disease compared to other associated diseases, such as rotavirus. BCoV infection occurs in calves between the ages of one week and three months and gastrointestinal signs include diarrhea, dehydration, depression, reduced weight gain and anorexia. Respiratory infection in calves shows as a nasal discharge and clinical signs may worsen with secondary bacterial infection. Infection in adults is normally subclinical, the exception being with winter dysentery, which affects housed cattle over the winter months. Clinical signs include diarrhea and a significant drop in milk yield.

Coronaviruses genetically and/or antigenically similar to BCoV have been detected from respiratory samples of wild ruminants, dogs (Erles et al., 2003) and humans (Zhang et al., 1994). A human enteric CoV isolate from a child with acute diarrhea (HECoV-4408) was genetically (99% nucleotide identity in the S and HE gene) and antigenically closely related to BCoV, suggesting that it is a BCoV variant able to infect humans (Saif, 2010). There are commercial BCoV vaccines to prevent enteritic disease in cattle but none are available against respiratory BCoV infections (Gomez & Weese, 2017).

References

- Boileau MJ, Kapil S. Bovine coronavirus associated syndromes. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2010;26(1):123–146.

- Erles K, Toomey C, Brooks HW, Brownlie J. Detection of a group 2 coronavirus in dogs with canine infectious respiratory disease. Virology. 2003 Jun 5; 310(2):216-23.

- Oma, V.S., Tråvén, M., Alenius, S. et al. Bovine coronavirus in naturally and experimentally exposed calves; viral shedding and the potential for transmission. Virol J 13, 100 (2016).

- Gomez DE, Weese JS. Viral enteritis in calves. Can Vet J. 2017;58(12):1267–1274

- Saif LJ. Bovine respiratory coronavirus. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2010;26(2):349–364. doi:10.1016/j.cvfa.2010.04.005

- Vijgen L, Keyaerts E, Lemey P, et al. Evolutionary history of the closely related group 2 coronaviruses: porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus, bovine coronavirus, and human coronavirus OC43. J Virol. 2006;80(14):7270–7274.

- Zhang XM, Herbst W, Kousoulas KG, Storz J. Biological and genetic characterization of a hemagglutinating coronavirus isolated from a diarrhoeic child. J Med Virol. 1994 Oct; 44(2):152-61.

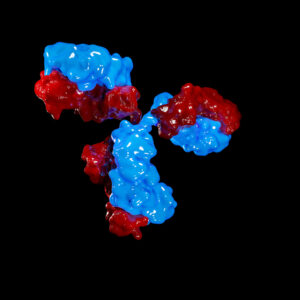

Bovine Coronavirus Antibodies

Questions?

Check out our FAQ section for answers to the most frequently asked questions about our website and company.