Candida Albicans

Candida Albicans Background

Candida albicans is the most common serious fungal pathogen of humans, causing 250,000 to 400,000 deaths per year worldwide and ~100 million episodes of recurrent vaginitis. It is a classical opportunistic pathogen residing harmlessly as a commensal in approximately 50% of individuals, and kept in check by our immune system and a protective bacterial microbiome of the gut and other mucosal surfaces (Da Silva Dantas et al., 2016). C. albicans can also survive outside of the human body. Within humans, it is a member of the healthy microbiota, asymptomatically colonizing the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, reproductive tract, oral cavity, and skin of most people. In individuals with healthy immune systems, it is kept in balance with other members of the local microbiota and is generally harmless. However, changes in the host microbiota (e.g., due to antibiotics), changes in the host immune response (e.g., during stress, infection by another microbe, or immunosuppressant therapy), or variations in the local environment (e.g., shifts in pH or nutritional content) can allow it to overgrow and cause infection. These infections are especially serious in immunocompromised individuals (such as those with AIDS or those undergoing anticancer or immunosuppression therapies) and healthy people with implanted medical devices (Nobile & Johnson, 2015). Recent studies also suggest that C. albicans can cross the blood brain barrier (Wu et al., 2019).

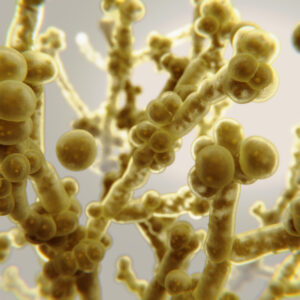

C. albicans is a polymorphic fungus and can transition between yeast and hyphal forms (dimorphism). It can grow either as an ovoid-shaped budding yeast, as elongated ellipsoid cells with constrictions at the septa (pseudohyphae) or as parallel-walled true hyphae. Other morphologies include white and opaque cells, formed during switching, and chlamydospores, which are thick-walled spore-like structures. Both growth forms are important for pathogenicity but the hyphal form has been shown to be more invasive than the yeast form (Mayer et al., 2013). C. albicans also grows as a highly structured biofilm, forming a community of adherent cells attached to solid surfaces, such as implanted medical devices, including catheters, pacemakers, dentures, and prosthetic joints or at liquid-air interfaces. Biofilms are often resistant to conventional antifungal therapeutics, the host immune system, and other environmental perturbations, and biofilm-based infections present a significant clinical challenge (Nobile & Johnson, 2015). Recent estimates by the National Institutes of Health suggest that pathogenic biofilms are responsible, directly or indirectly, for over 80% of all microbial infections (Nobile & Johnson, 2015). Resistance to anti-fungals is increasingly becoming a problem, particularly as there are only a limited number available. One of the problems in developing more is that in contrast to bacteria, fungi are often overlooked as a potential health problem (Nat Microbiol., 2017).

References

- Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 2013;4(2):119‐128.

- Brown GD, Denning DW, Levitz SM. Tackling human fungal infections. Science. 2012 May 11; 336(6082):647.

- da Silva Dantas A, Lee KK, Raziunaite I, et al. Cell biology of Candida albicans-host interactions. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;34:111‐118.

- Nobile CJ, Johnson AD. Candida albicans Biofilms and Human Disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:71‐92.

- Wu Y, Du S, Johnson JL, et al. Microglia and amyloid precursor protein coordinate control of transient Candida cerebritis with memory deficits. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):58.

- Stop neglecting fungi. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17120.

Candida Albicans Antigens

Questions?

Check out our FAQ section for answers to the most frequently asked questions about our website and company.